The European Commission, a permanent executive branch of the European Union, wants a more streamlined and focused manner to invest and maintain important space programs and proposes to give itself the means to do so by drafting a budget regulation, which, if adopted, would put several important space programs on a stable footing.

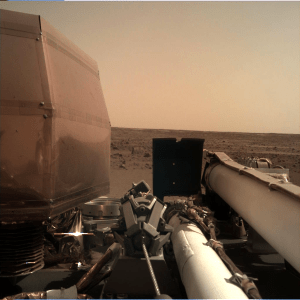

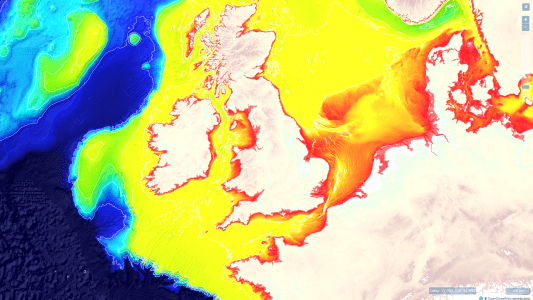

The proposal would provide the Union with a space budget of a sufficient size to carry out the various activities envisaged, in particular in respect of continuing and improving Galileo, EGNOS, Copernicus and SST, as well as launching the Govsatcom initiative.

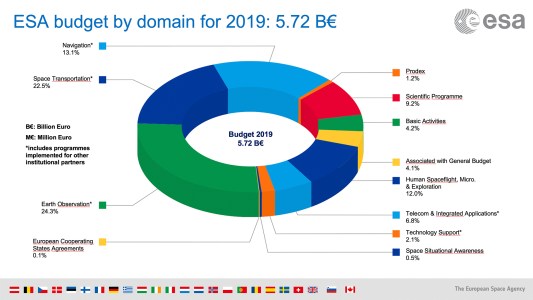

Worse for ESA, the regulation proposes a budget of EUR 16 billion for the project, for the period 2021-2027, compared to ESA’s annual budget of EUR 5.25 billion. This means EU immediately entrusts this programme portfolio with the equivalent of half of todays’ ESA budget, in the mentioned period. Leadership of ESA was not required.

To do the same, the intergovernmental agency ESA would have to convene a ministerial council, usually biannual, which would give budget envelopes usually spanning only parts of the project. The result is an inefficient, lengthy process, with an uncertain outcome. The reason is that during each negotiation ESA is handicapped by the election and budget cycles taking place within its member nations who always have the discretionary right to decide if and how many funds they will provide. This contrasts starkly with the European Union which has a stable income allowing it to allocate budgets with more stability over longer periods. Furthermore, the members of the European Commission, appointed permanently, are bound to act independently – neutral from other influences such as those governments which appointed them. (Contrary to a EU council or even a ministerial ESA council)

While the regulation goes to great length to sidestep and neutralise the issue, if adopted it heralds a precedent where ESA and the EU become institutions competing for the same projects and national funds either directly or indirectly. If the regulation is implemented successfully - and in a commercial space market there is no real reason why it shouldn’t -, the projects listed could only be the beginning of an expansive EU space policy slowly eroding the wider activity portfolio, importance and budget of ESA. Countries might argue during ESA negotiations that they already provide a certain level of funds to the EU a percentage of which would be allocated to space activities and hence don’t feel inclined to hand out more to ESA.

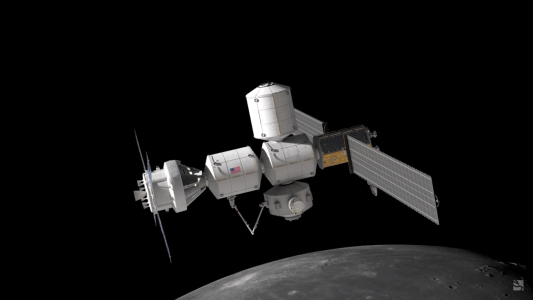

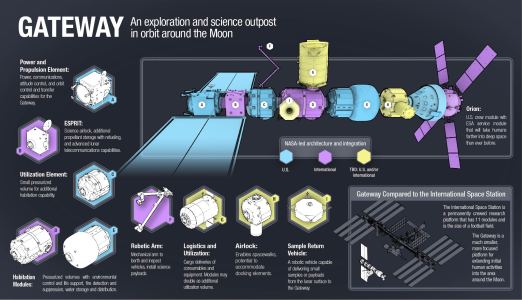

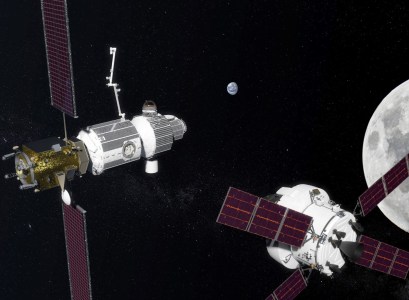

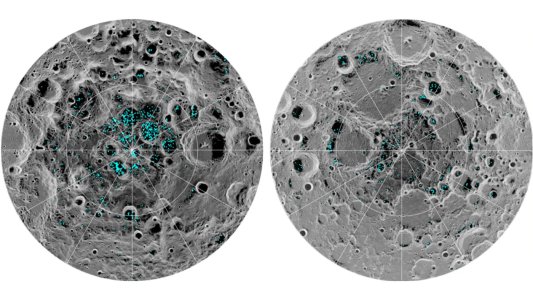

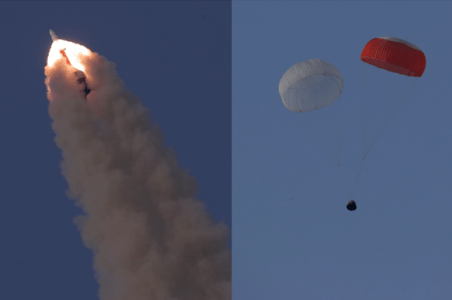

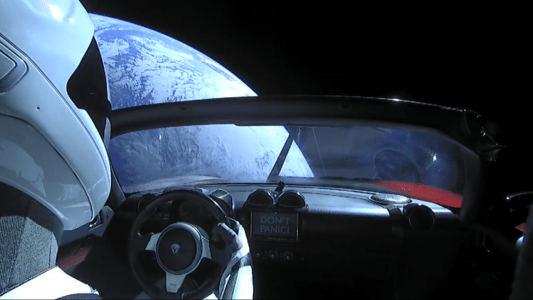

It is no surprise that ESA boss Jean Woerner unhappily defends the interests of ESA, -as any head of an organisation would-, diplomatically calling the initiative an unnecessary duplication. While ESA has had its historical technological successes (like landing on a comet, on Titan, launching modules to the ISS, or providing the service module for the moon capable NASA Orion) there is no good argument why ESA would be a more effective administration than an EU lead one. Even if it is true that ESA has non-EU members in its ranks, these non-members could also cooperate in EU lead programs on an equitable footing.

- For the text of the draft regulation (Comission) and press release (RAPID):

- An in-depth response on Jean Woerner’s personal blog:

Lastly, while the EU communicates the desire to become a more ambitious, stronger space power and cement an autonomous European Space capability, the principe de « juste retour » or equitable geographic return, embedded in the ESA financial and programmatic decision-making system, might finally become less of a burden for a truly open European commercial space market where the customer benefits from the cheapest and most competitive commercial product. Just retour favours the creation of only a handful of oligopolistic government contractors, specifically sequestered in activities in order not to compete, and who’s organisational and technical imagination only stretches to create products deemed good enough to become the winner of a public tender. In the current New Space environment, this handicap from the past, more focussed on creating capability and protecting competing national interests than to provide customer value, is proving a dead knell on fast and commercially competitive innovation.

The regulation does not have language that completely establishes an open space market in the areas of focus, or eliminate juste retour, but the EU, as a more democratic and not a purely mandate driven intergovernmental institution like ESA, is more prone to political self-criticism and might be able to eventually dismantle the juste retour idea in a business area whose commercial and civilian value and importance to the bottom line of the EU area, is starting to outstrip the monetary value in the purely strategic and military space markets.

Traditional large European space companies will see the regulation as a wake up call, but it will also provide them with a lot of business opportunities as the mentioned programs now become institutionalised with a stable budget and might expand.

Indeed, ESA might suffer in the long run, but a positive note is that a new more democratic institution might result from the shift, more open to sensible commercial arguments and reflexes. In any case the technologies and businesses will remain European and the space activities sector will grow.

For more background and in depth analysis, see the 1 hour video: “EU 10th Conference on European Space - “More Space for more Europe”, ProductiehuisEU, dated Jan 23, 2018.