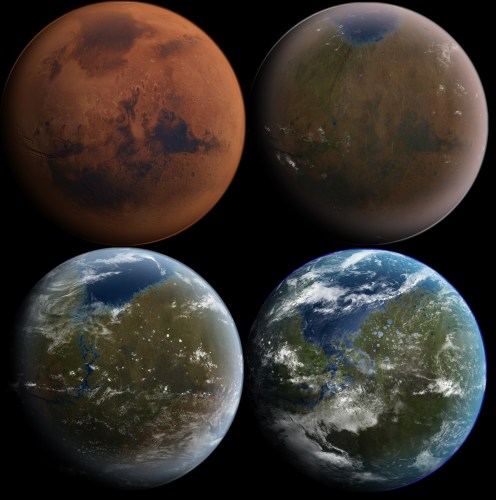

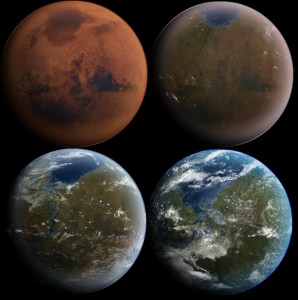

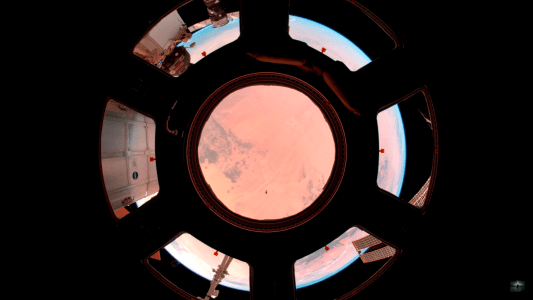

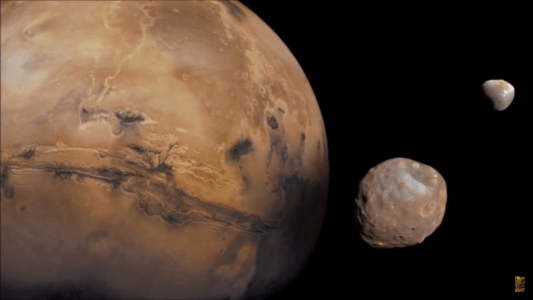

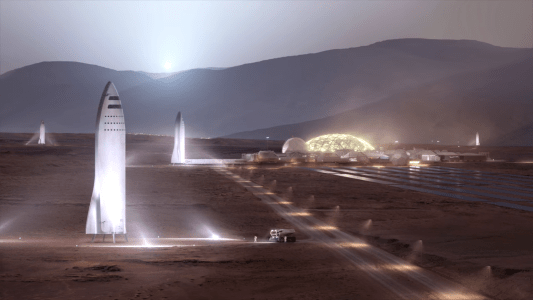

(image credit: Daein Ballard - CC BY-SA 3.0)

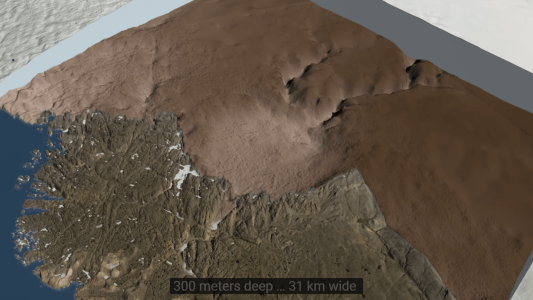

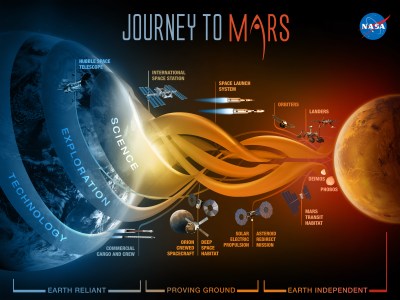

Mars. Another human colony or a biological hazard zone forever made off limits for humans by planetary protection rules? Somehow I believe insights will evolve and Mars will indeed not become a forbidden planet, but another node in the interplanetary human network of thriving settlements. It has the resources for large colonies and it would be a waste not to use them.

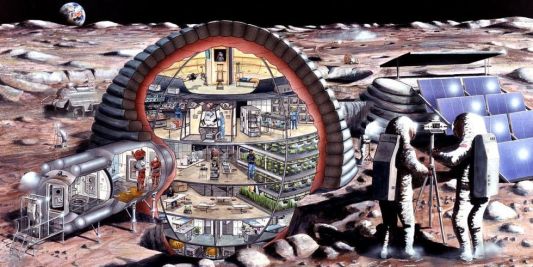

But some of those resources are limited. Sure, we can turn them into propellant, breathable gases, plastics, fertilizer, and metals, but with regards to the ones we can get from the Martian atmosphere, there are not enough of them.

Indeed, there is only so much CO2 to compress into city size habitable domes, a scheme called para-terraforming, before you run out. This could cause problems, not only for the Martian environment, but it could even hinder shipments to Mars, which would no longer have an atmosphere to slow their orbital velocities and would see a dramatic increase in propellant needs, since even the thin Martian atmosphere can slow a ship down for free with >90%. We probably will not allow this to happen.

At the same time, there are doubts the business case will be there to import CO2 and other gases to MARS on a planetary scale (e.g. from Venus, which has 90 BAR worth of it in a mix of CO2, N, and H). The advantages of doing this are obvious. Mars would warm up. The radiation protection would be as good as on Earth. Rivers would start to flow. Plants and humans would thrive without requiring oxygen masks, domes or pressure suits. A small Eden would be created which, with its lower gravity, could be an ideal retirement home for the elderly.

So what is the solution?

First, you would import only the urgently needed and noble buffer gases from other celestial bodies. Gradually these transport routes will become more established, expand and become common.

Forward-looking entrepreneurs could organize the import of Nitrogen from the Venusian atmosphere, which has too much of it, and provide fertilizer for agricultural food production in the existing domes on Mars.

So yes, a small industry to supply relatively small domes with imported resources will eventually take off. The question is, is there an important enough business case to terraform an entire planet?

(For a break down of the business plan cost of a possible engineering approach to this problem, take a look at our article “Terraforming Mars impossible? Not so fast: It only takes 40 Apples to turn Mars into Eden.“)

The more ambitious real estate agent and the Dutch nationals who rid their country of water will nod affirmatively, but even they would admit that the scale is beyond pharaonic. Nevertheless, small steps can grow into large strides. In Holland, the Dutch started draining small private pieces of land and marshes before their isolated victories over the water gradually turned into an even more ambitious project of national importance. The surprise is that it eventually only took two centuries to drain the entire country. In the Dutch case, the economic benefits that were noticed when small plots of land were drained, were enough to gradually convince an entire nation to follow suit. Still, a country is not a planet.

In the same vein, we understand there is a small expansive business case to supply Martian domes with gases. But the question remains: how could we make this gradual approach scale to the entire planet of Mars?

A terrestrial case study

For inspiration on a workable example of how we can come to terraform Mars, we needn’t look far. Simple concepts from the modern phenomenon of global environmentalism are good enough. There, to address complex issues, humanity often works with vague plans.

For instance, what was the Business Case for Carbon Credits? In any case, the derived Business Cases (afforestation, carbon capture, reduction) were the result of installing a legal regime that created artificial scarcity where there was none. Polluting companies were given a permit to vent only a limited and decreasing amount of CO2 into the air, which would entice these businesses to pollute less. These rights can also be traded. At the opposite end of the scale, businesses receive money for permanently removing C02 from the atmosphere and prevent it from acting as a greenhouse gas.

In a more abstract manner, the legal regimes they install could all be explained in terms of being business cases to buy future agricultural productivity. Even if this is a crude oversimplification not doing justice to the inherent value of nature or a habitable climate, for economists it has the advantage of turning environmentalism into a quantifiable business rationale.

Nevertheless, to have any meaningful effect, these legal regimes need to be in place for decades. You can even argue they need to be in place for centuries since for all our current received wisdom, natural warming processes we do not yet fully understand could play an unrecognized role.

If, after 200 years of further research, C02 turns out not to be the main culprit, efforts to create an ‘ideal’ world climate will probably continue, because we will have become accustomed to the idea that something as an ‘ideal’ climate, with a less chaotic nature, is not only beneficial to our survival, but something we ought to create to prevent the impracticalities and xenophobia that come with the streams of climate or drought refugees. Further, it could help to prevent the shifting of animal migration patterns or to protect the food security and even tax income of a nation.

In any case, combating climate change or the quest to dial in some ‘preferential stable climate’, for better or worse, is a form of geoengineering, even terraforming, that we have decided to engage in as a global community.